The Berlin Marathon Experiment

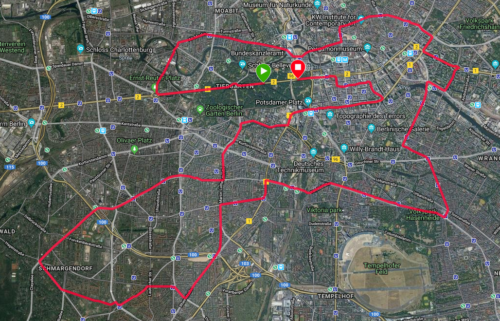

The distinctive map of the Berlin marathon course

The distinctive map of the Berlin marathon courseAim

To take an over-the-hill, middle-aged, untrained male subject to a level of conditioning appropriate to completion of the Berlin marathon (for inline skaters). A secondary aim of him earning a qualifying time for the A starting block at next year’s event is also considered.

Method

A training program lasting 8-weeks was written and followed, subject to the time constraints imposed on the subject.1 At the end of the 8-week time period, the subject participated in the Berlin marathon, and his time recorded.

The Constraints

Chief among the subject’s time constraints was the fact that he had inexplicably been entrusted with the care of a very small child. Part of the reason for this might be that the child is his own, but this discussion is beyond the scope of the experiment.

By the time of the start of the experiment, the child had recently become a regular attendee of daycare, so the subject was unencumbered between the hours of 9:00 and 15:00 on weekdays (though realistically 9:30 and 14:30). During this time, the subject could travel to and from training, train, shower, etc. but also had to complete various errands (e.g. picking packages up from the post office), eat lunch, complete contracted (paid) freelance work, and nap.2

The other major constraint was sleep. While it is well-understood that athletes in training require generous amounts of sleep in order to adequately recover, and during which training adaptations occur, the care of sub-2-year-old humans is generally not conducive to long nights of continuous sleep. This challenge was overcome by disciplined adherence to regular naps in the middle of the day.

Program Considerations

Despite being untrained, the subject has had, from his past, a long training history which had to be taken into account when writing the program. For example, this was not the first time he had ever inline skated. He had been to world championships as a competitor on three occasions (the first in 2003, and most ‘recently’ in 2007). He has also competed at the university level in athletics.

More pertinent to the analysis of training needs for this program was also the fact that, when he was training and competing in both inline skating and running, the distances in which he specialised were at the short end of the spectrum. The longest distance he ever ran at university games was the 800m, typically a 2 minute effort, and the longest distance he would be considered good at in either ice or inline skating (when in a well-trained state) was the 1500m (tellingly, also a 2 minute effort). A cursory survey of his contemporaries revealed further that our subject performed relatively better at the shortest distances, presenting an additional challenge to programming for a marathon.

Despite our subject being physiologically better-suited to shorter distances, typically ranging from 11 seconds to 2 minutes (and being better at the shorter efforts), the fact remains that the marathon distance is typically covered by elite skaters in an hour, and sub-elite skaters in anything up to 1:15 – a far cry from 2 minutes. On the plus side, his racing history suggests that high speeds (at least for short periods of time), fast accelerations, and jostling for position in pack-style racing are familiar to him, removing some of the common obstacles faced by middle-aged skaters trying to do well in the marathon.

At our disposal for the purposes of training were a disused airport, a road bike with power meter, a public gym with a well-equipped free weights section, and any number of parks close to the place of residence of our subject for running or doing plyometrics.

In addition, it had to be taken into account that coming from an untrained state would require some “equipment acclimatisation”, that is getting the feet used to being in a pair of skates and allowing the skin to thicken around the heel and arch for example, or allowing the soft tissue near the sit bones to acclimatise to a bicycle seat for the lengths of time necessary to acheive a training effect.

The Program

With the aforementioned constraints and considerations in mind, it was decided to construct a simple program of 7-day blocks with one rest day, moving to two rest days in the final weeks of the training taper. Variations in training load were accomplished by varying the number of sets within a given workout. The workouts would be broken down as 2 skates, 2 bike rides, and 2 runs.

The simplicity was necessary because, owing to the subject’s untrained state, we could not afford to waste more time than necessary getting him used to different training paradigms (most of these sessions would necessarily be different to what our subject was used to, given the nature of the event being targeted). Resistance weight training was deliberately omitted because the length of time required to acclimatise, and the types of adaptations which could be quickly gained meant that the return on invested time and effort was significantly lower than the other training modes for the purposes of this experiment.

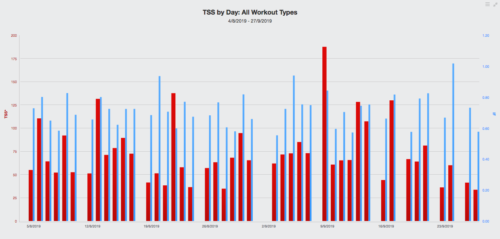

TrainingPeaks’ training stress scores (training load) plotted with intensity factor. The training blocks within the 8-week period can be clearly seen

TrainingPeaks’ training stress scores (training load) plotted with intensity factor. The training blocks within the 8-week period can be clearly seenThe 8-week period was broken down into blocks of: hard, hard, easy, hard, hard, overload, easy, and easier – the final two weeks being a standard short training taper. The weekly structure broken down by day is as follows:

Monday

Inline skating at Tempelhof Airport.

A lap consisting of nearly the full length of both runways and the taxiway in between (approximately 5km) to warm up.

Throughout Tempelhof airport these Gran Tourismo-style markings mark out distances along the runway, allowing for easily-measured interval training

Throughout Tempelhof airport these Gran Tourismo-style markings mark out distances along the runway, allowing for easily-measured interval trainingStanding 500m with 90 seconds recovery x8. Done at an effort which exhausts the subject by the end, but still allows the 500m times to be within a second of each other. Ordinarily done at 85-95%

These were done at the beginning of the week when the subject was most fresh and rested, as it was the most intense workout and presented the greatest amount of stress on the nervous system. This hopefully allowed us to maximise the quality of what was the most technical workout of the week.

Depending on wind direction and speed, the difference in times between odd and even numbered intervals can be great, and measuring the effort to be consistent throughout all 8 presented an additional challenge.

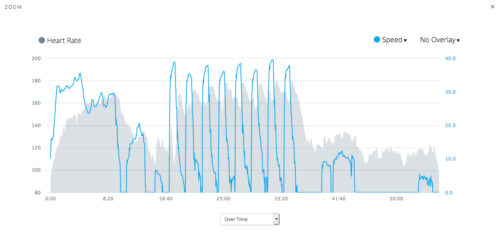

A typical graph of speed and heart rate for Monday training. you can see the warm up (and the speed difference between headwind and tailwind directions), moving to the start of the interval, and the difference in speed between intervals done into the wind, and with the wind.

A typical graph of speed and heart rate for Monday training. you can see the warm up (and the speed difference between headwind and tailwind directions), moving to the start of the interval, and the difference in speed between intervals done into the wind, and with the wind.Tuesday

Cycling on the bike trainer.

The “hour of power”. An hour holding a wattage (regardless of heart rate) at functional threshold power (FTP) – often defined as the maximum wattage one can hold for an hour.

The reason for this workout should be obvious. Not only is training at close to lactate threshold a useful thing to do for lactate tolerance (tolerating that burning sensation you get in your muscles as a result of intense exercise), but for a skater with a target time, the marathon basically amounts to a 42km time trial. In practice, our subject would expect to be able to spend some (indeed most) of the race in the peloton, shielded from the wind, but having the confidence to be able to push out a hard, hour-long effort is invaluable for the type of race that an inline marathon often is.

In practice, we made the mistake of estimating the subject’s FTP based on past training data (as we had no “current” data) and went too hard in the first session, and had to cut it short. Eventually, a reliable FTP estimation was arrived at which we were able to use in the modified version of this workout, during the taper.

For the training taper (the final 2 weeks leading into the event) the Tuesday program is a little different. A literal reduction in volume and increase in intensity is accomplished by halving the workout time, and following the over-under pattern of 6 minutes at about 30 watts above FTP followed by 6 minutes at about 30 watts below FTP, finishing at the end of a hard interval. This was done in the second to last week before the race. In the final week, the time was reduced to 5 minutes over-under but 40 watts above/below FTP, but still completing 30 minutes, so finishing on the “easy” interval.

Wednesday

Running around the park.

A loop of approximately 2.5km was established at a nearby park and the subject instructed to run 4 laps at an easy pace.

The challenge of this workout was ensuring that the subject kept the intensity low enough to target the correct energy system.

The monotony of trudging along at an easy pace is too easily broken by trying to go faster so a system of calming podcasts was implemented whereby the subject would be able to focus on listening, and complete his run at the correct intensity as a background task. The VeloNews Fast Talk podcast, 99% Invisible, Behind The Bastards, the BBC’s More or Less and 50 Things, as well as the Due Power Podcast all come recommended.

Thursday

Cycling indoors on the bike trainer.

2 hours at an easy pace – about 50% of FTP. Low cadence.

Conventional wisdom tells us to pedal a bike at around 80rpm, or slightly faster. Studies have shown that lactate clearance is best at between 95 and 110rpm. But skating takes place at a much lower cadence, so in the interest of specificity, we set the resistance in such a way that the cadence that achieves the desired wattage for the ride comes to just over 60.

2 hours of riding at the same, easy pace is probably even more boring than running 10k at 10km/h, but luckily in the controlled environment of a home trainer at home, we overcame the boredom by setting up a small home theatre by using an ipad mount, a portable battery-powered speaker, and a lot of films which are about 2 hours long (with subtitles so that the dialogue could be followed above the noise of the bike’s drivechain and cooling fan).

Although time-consuming and, from the point of view of training, uninteresting, the long slow rides gave our subject an opportunity to watch many films he had been meaning to watch, but hadn’t yet had the opportunity

Although time-consuming and, from the point of view of training, uninteresting, the long slow rides gave our subject an opportunity to watch many films he had been meaning to watch, but hadn’t yet had the opportunityFriday

Inline skating at Tempelhof airport.

4 of those 5k (ish) laps of the airport at an easy to moderate pace. 2 minutes recovery in between.

The screenshot of the TrainingPeaks analysis page for a typical Friday workout

The screenshot of the TrainingPeaks analysis page for a typical Friday workoutAgain, it was difficult to ensure a low enough intensity to target the aerobic energy system. The interesting thing about this particular workout was that, as far as the leg muscles were concerned, this was mostly an easy aerobic workout, but for the muscles of the lower back and core, it was a moderately difficult interval.

Saturday

Running around the park.

This is a repeat of the workout from Wednesday.

Sunday

Rest day. For the final two weeks leading into Berlin marathon, Wednesday was also a rest day.

Program Objectives

Those observant readers will notice that the training program follows a polarised(ish) training paradigm.3 This was chosen for several reasons. Coming into the program untrained meant that our subject had no aerobic base, and since most of the workouts in a polarised training program are targeted at the aerobic energy system, this seemed to fit our needs. Coming into the program untrained also meant that adapting to high intensity interval sessions placed a larger than normal stress on our subject’s physiology so it was important to minimise the number of those sessions while still maintaining training frequency and volume, lest we run the risk of overtraining and burnout, not so much from the training volume (which is low, relatively speaking) but from having to quickly adapt to, and recover from many high intensity sessions. The risk of injury is also minimised in this way.

The program was also specifically designed to target the PGC1-alpha regulator mechanism which plays an important role in adaptation for endurance events. Although 8 weeks is a very short time, it was hoped that increased adaptation of the MCT1 transporter (responsible for clearing lactate out of the bloodstream), as well as higher blood plasma volume would result from the longer training sessions. The net result of these adaptations over time should be a slight improvement in VO2 Max.4

Spacing the two skating sessions far apart and at points in the week when the subject was supposed to feel more rested was hoped to maximise the quality of those workouts and allow the subject to gain confidence in his technique, which was rusty after a prolonged absence from training.

Monitoring

All of the training was recorded on a Garmin Forerunner 945 sports watch, and uploaded to Garmin Connect which in turn passed the data into the subject’s TrainingPeaks account which allowed documentation of as many of the measured parameters as possible while also allowing the subject to record more subjective measures such as perceived effort and tiredness. It also allowed for an easy way to keep track of chronic and acute training load which helped us avoid a situation of accidental overtraining from a too-rapid increase in the training load.

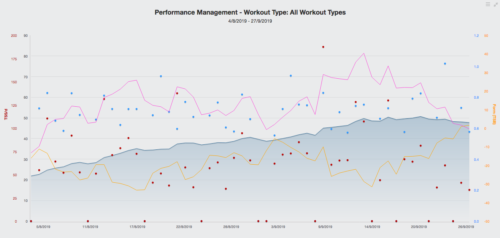

Keeping track of acute training load (pink line) and chronic training load (shaded blue area) to ensure no overtraining

Keeping track of acute training load (pink line) and chronic training load (shaded blue area) to ensure no overtrainingIn addition to the watch’s GPS collecting data on speed during the runs and skates, heart rate data was collected on all workouts, and power data for all cycling workouts. Power was collected via a recently calibrated crank- mounted Quarq power meter, and heart rate was collected using a Whoop strap mounted on the left bicep.5

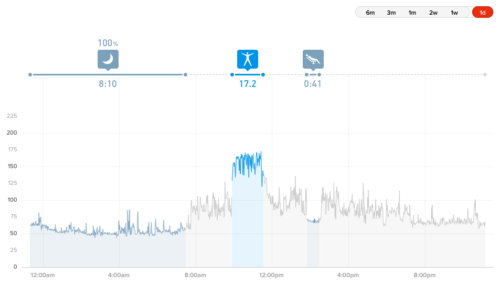

A typical 24-hour period monitored by the Whoop strap, showing sleep score, workout strain score, and nap duration.

A typical 24-hour period monitored by the Whoop strap, showing sleep score, workout strain score, and nap duration.In addition to the workouts themselves, the bicep-mounted Whoop strap collected heart rate data 24 hours a day (it is designed to be worn 24 hours a day), heart rate variability (HRV) data 24 hours a day, and sleep data. Using a combination of sleep data, resting heart rate, and heart rate variability, the Whoop also calculates a “Recovery Score” which gave the subject an indication of his recovery and fatigue status on any given day.

Although not originally intended as a sleep monitor, the Whoop is one of the best ones that the subject has ever used

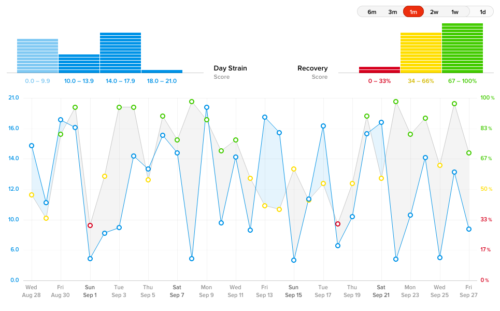

Although not originally intended as a sleep monitor, the Whoop is one of the best ones that the subject has ever used Whoop strap calculated day strain scores plotted with recovery scores over the 4-week period prior to the Berlin marathon

Whoop strap calculated day strain scores plotted with recovery scores over the 4-week period prior to the Berlin marathonThe continual monitoring of the subject’s physical parameters allowed us to avoid overtraining, anticipate sickness, and know when it was or wasn’t a good idea to push through when the subject felt tired.

Notes on Execution

Giving an athlete a program without any allowance for feedback or adjustment would be irresponsible, and expecting everything to go exactly according to plan would be unrealistic. That being said, the training program went surprisingly according to plan. There were however, some hiccups.

In week 3, the realisation hit early on that easy week wasn’t easy enough. The variation in training load was achieved by varying the numbers within each workout, for example the ‘normal’ number of 500m intervals on Monday was 8, and so during easy week it was set to 4. Of course, psychologically when an athlete is faced with only 4 intervals instead of 8, and had become accustomed to measuring his effort in such a way that near- exhaustion is reached at the end of the session, then one can expect the set of 4 to be done at a higher intensity than the set of 8. Both stopwatch and heart rate data confirmed that this is what, indeed, had happened, and even though the overall training load was still lower, the stress on the nervous system was considerably higher, and this showed up in the HRV data.6

Towards the end of week 5, HRV took an unexpected dip which was followed by a spike in resting heart rate. Low level symptoms of illness were also observed, but these are common during hard training blocks. Using the data, the decision was taken to drop Monday’s training and take a second consecutive rest day instead to recover further from illness (in case anyone is wondering, you should never train while sick). That week, the Tuesday and Thursday bike rides were swapped (the long 2-hour ride has the lowest training stress of all the sessions), and training otherwise resumed as normal. Thanks to the power of data, only one training day was lost at a time when a prolonged illness could have easily cost our subject a week or more of training.

Results and Discussion

The most well-prepared race bag still can’t stop the rain

The most well-prepared race bag still can’t stop the rainUnfortunately, one of the things which didn’t quite go to plan was the weather. Whereas in the program, we were able to easily swap sessions and days according to weather conditions (only the skating sessions needed dry weather), the date of the Berlin marathon is fixed over a year in advance and affords no flexibility. The heavens opened about half an hour before the start and soaked the course and skaters thoroughly for the duration of the event. Our subject placed 57th among non-A-group skaters, and 15th in his (middle) age category. As an indication of how much the rain can slow things down, winner Felix Rijhnen completed the course in a time which was two minutes slower than the qualifying time for the A-group starting block, and a full 10 minutes slower than the typical time for the A-group peloton. For those who are curious, a link to the data from the marathon itself is available here.

There were, however, some positives to take away. Post-race analysis has shown that our subject was, indeed, in better condition for a skating marathon than on any previous occasion. In the past, even when trained (recall that his preferred racing distances were short sprints) he would typically skate the marathon by hiding in the peloton then try to do well out of a pack sprint for the finish. Previous attempts at the marathon have revealed our subject to often have enough of a top speed advantage to get a small jump on the B-group pack, although lacking the strength to stay away, and certainly lacking the strength for a strong, persistent sprint all the way to the line. Previous starts in the A-group for our subject (and at World Championships in his younger days) have seen him dropped early in the race, often within the first 10k. On this occasion, although suffering from a poor start while acclimatising to the conditions, he was able to expend generous amounts of energy bridging gaps and clawing his way to the second B-group pack, where he was able to begin his sprint from over 1km from the line, and finish strong to nearly but not quite win the bunch sprint, surprising himself in the process.

The subject brought along his own skate technician

The subject brought along his own skate technicianIn conclusion, despite not reaching the target time, the experiment was a success overall with our subject making significant and measurable physiological gains as an endurance athlete, despite his advanced years. With small modifications, and using the lessons learned from this experiment, we hope to apply a similar (but longer than 8 weeks) program to the ice speed skating season to see how it affects our subject’s performance in the shorter distances that he ordinarily races – 500m, 1000m, 1500m, and 5000m – all significantly shorter than the marathon.

Footnotes

- There were small deviations from the original training plan, and those are discussed at length later in the article ↩

- Naps weren’t extrinsic to the program like the other tasks described – they were, in many ways, a part of the training program, as will be discussed later in the article. ↩

- Polarised training follows an approximate 80-20 ratio of “easy” aerobic sessions to hard, high intensity interval sessions ↩

- VO2 Max is the maximum rate at which an athlete can metabolise oxygen in the aerobic energy system, and is an important indicator for the ability and conditioning of an endurance athlete. Elite endurance athletes typically have values in the 70s and 80s, our subject was once tested to have a VO2 Max of 45, although the test was halted prematurely due to our subject’s unusually high maximum heart rate. ↩

- The Whoop strap is actually designed to be wrist-worn, but as an optical heart rate monitor, a more consistent and accurate reading can be collected when the monitor is worn on the upper part of the arm as the skin is thinner, lighter, and there is less movement. ↩

- HRV measures the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, so while it’s a good proxy for stress in general, it is a very good indicator of stress on the nervous system. ↩

Leave a comment