PhD Ideas

© Matt Might (from the Illustrated Guide to a PhD)

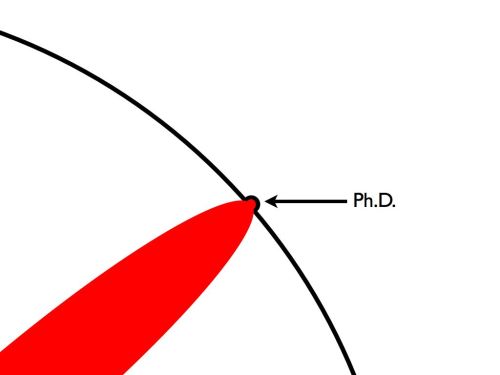

I’ve spent several years in the ‘real world’ now, travelling and working, and while it has been fun, it has also made me realise how curious and how academically-minded I am (I’m the annoying guy who sits in meetings and thinks far too much about everything). With this in mind, I am seriously considering going back to school and perhaps taking up PhD studies. I have in the past applied (unsuccessfully) to PhD programmes, and I believe that part of the reason for this lack of success is because, while I certainly have a mind for research and the requisite curiosity, I wasn’t specific enough in my research ideas. A PhD is fundamentally about doing research – not only learning new things, and expanding one’s own knowledge, but of learning new things and expanding the body of knowledge that exists in the world. I’ve become rather disillusioned with the world of academia and the attitude of “publish or perish” which basically encourages large volumes of mediocre work rather than small amounts of really significant work. All thanks to the insane mindset of trying to run a university like a for-profit business. In any case, I’m not too fussed where I do it (although I would like to do it somewhere near Copenhagen, if possible, because I’m sick of moving), I just want to find some good supervisors, and actually do some meaningful research.

I’ve outlined some topics below (indeed, some of these paragraphs read like abstracts) in the hope that someone might know someone who might know someone, or that friends of mine who are more experienced in this business of doing PhDs and academic research in general can help me possibly refine my research interests, or find good supervisors or departments to contact.

Economic Information

This one has been bouncing around in my head for a while. Economics is a relatively young and immature (in more ways than one) science and this is part of the reason its predictive power hasn’t been great. Still, that doesn’t mean that we’re completely clueless, and a lot of good and interesting work has been done. We’re slowly coming up with more robust theoretical frameworks, and coming up with theories whose assumptions are much weaker (making the theories stronger… it makes sense if you think about it).

Information economics is relatively new in the scheme of things. The 2001 Nobel Prize for economics was awarded to three pioneers in the field who studied the behaviour of markets with asymmetric information. Insurance markets where the buyer has the advantage, and the seller ‘screens’, used-car markets where sellers have the advantage, and the job market where signalling takes place to exchange vital information are all examples. Previous theories concerning the behaviour of markets often assumed zero transaction costs and perfect information, and while in many cases transaction costs are indeed very low, perfect information is actually quite rare. Studying information asymmetries gives us greater insight into why these theoretical models so often fail us in the real world.

I want to look at information costs, and the transmission of information in general in complex transactions. Take the subprime mortgage bubble-burst for example. Many things went wrong (there’s a great video explaining it all here) but at the heart of this market failure was the fact that people were buying into products which they did not fully understand. Everything else (and there was a lot of other ‘bad stuff’) served to amplify the effects of the crash and connect it to the rest of the world, but fundamentally consumers were taking on more risk than they were aware of.

In small scale economies, markets function very well because everyone knows each other and everyone knows everything. You know what you’re buying and selling, you know the guy you’re buying or selling from, it’s easy to work out checks and balances for large transactions. However, in modern globalised economies, even everyday transactions can be horrendously complex behind the scenes. There’s scale – how many people are in on a transaction, network complexity – a product being repackaged and sold on, recombined and sold on, etc, and the dimension of time – buying a sandwich is a relatively short-time transaction as opposed to something like life insurance.

When information costs and uncertainties are better-understood it can help us calculate risk better. Humans are demonstrably terrible at intuitively dealing with uncertainty (which is why lotteries still exist) so having the right theoretical tools to deal with information uncertainties in economic transactions would be very valuable in preventing future large scale market failures. Depending on the kinds and nature of these tools, we may be able to weed out agents who are acting dishonestly, or construct incentive structures within, say, the financial sector which would discourage the unnecessary taking of risks (with other people’s money).

Linguistic Genome Tracing

It is well known amongst my friends that I have a tendency to get into arguments with people on the internet. Aside from honing my rhetorical skills in preparation for a possible future career in politics or talkback radio, it has given me a chance to observe the argumentative ‘skills’ of others.

The most common topic in which I find myself arguing is, not surprisingly, climate change (for my views on that, click here). Climate change is something I happen to know a lot about. I’ve studied climate science at the graduate level, as well as issues surrounding it such as natural resource economics, diplomacy, and sustainable development. Outside the bubble of academia, I’ve worked in UNICEF’s climate section, as well as the NGO Worldwatch Institute, with which I travelled to the Rio +20 summit and moderated a panel. Climate change, and the many different aspects relating to it is something I know quite a bit about, and from many different perspectives.

Something I’ve noticed in my various discussions is that people say the same things a lot. Obviously, when you’re debating a specific topic, it’s likely that the same arguments will come up, but there’s more than that. Many people actually say the exact same thing. I have a theory that arguments have ‘genes’. Not in the sense of actual DNA, but that the ideas obviously get passed down, but the transfer of information even occurs at the level of individual word combinations. (It could very well be the case that there isn’t actually enough information contained in the world of internet comments to be able to do this kind of genealogy trace)

I believe that, with the right kind of analysis (and with suitably large blocks of text), we can trace arguments over the internet in much the same way that genome sequencing confirmed the out of Africa hypothesis. My contention is that those arguing on the side of climate change denialism get their arguments from a small number of key sources (which, not coincidentally, are in the pocket of the oil industry) while those arguing on the side of climate change action get their arguments from a wider variety of different sources. I guess what I’m really trying to say is that climate change deniers are the rhetorical equivalent of inbred country hicks.

But in all seriousness, these linguistic-tracing tools would be very useful. You could trace arguments back to their source and then ask whether the source really knows what’s going on. Tracing the arguments of anti-vaccination campaigners would be a fun exercise, since we actually know where a lot of those arguments originate, as well as the source of that single, now-debunked, scientific study linking the MMR vaccine to autism.

Cryptography in Society

Big data is a big deal, and it turns out that big bad government agencies are reading yours. The impact of the work done in Bletchley Park to decrypt the German Enigma code is well documented, but how has encryption (or the lack thereof) impacted the lives of ordinary civilians in peacetime? Cryptography enables now-ubiquitous online banking and credit card transactions to take place, but has it had much impact beyond that?

With the introduction of systems like PGP in the early 90s, very powerful encryption is now easily available to ordinary people. However, even in light of the Edward Snowden leaks, the adoption of strong cryptography among the general population is still very low. Moreover, the systems in which we entrust vital information: banking details, medical records, and personal correspondence like email, are organised in large, centralised systems which are, from a structural standpoint, easier to compromise than say, a decentralised system.

The question remains. Has encryption helped society-at-large? People tolerate encryption and the accompanying security procedures for tasks like online banking, but voluntary uptake of things like email encryption is low outside of professions where there is an obvious interest (software engineers) or need (journalists). If not a tool for the wider population, has strong encryption helped governments function better? Worse? Has it lessened transparency, or (paradoxically) helped it? Is it possible that the only real benefit to society from widely available strong encryption is the protection of journalists and sources operating in dangerous environments?

This topic is broader than the previous two because I haven’t yet done a very thorough investigation into what research has been done, and where I might best apply my time. I’m also unsure as to whether there is sufficient material here to justify a PhD.

As a side-note, it might be fun/worthwhile to develop an entirely new cryptosystem. With symmetric key cryptography, the encryption function and decryption function are inverses of each other, and you can make the system as complex as you like, BUT securely exchanging keys leaves open a potential weakness in the cryptosystem. When you consider public key cryptography, it depends on a public and a private key – the public key encrypts the message (but can’t decrypt it) and the private key decrypts it (but can’t encrypt it). The keys are (obviously) related and it is not impossible (although it is very difficult) to figure out the private key using knowledge of the public key. What I’m envisioning is a different type of symmetric cipher which works like so – Alice encrypts her message with her key – function A, then sends it to Bob. Bob encrypts the encrypted message using his key – function B, then sends it back to Alice. Alice then decrypts the encrypted message using the inverse of function A – the message is still encrypted at this point, then sends it back to Bob. Bob encrypts it with the inverse of function B and finally ends up with unencrypted text. This encryption would be stronger because it retains all the advantages of a symmetric cipher, but also allows each participant to keep their private keys as secure as they are able. The only disadvantage is that the message has to be sent back and forth several times, or alternatively both communicators must be online simultaneously. The difficulty in coming up with such a cryptosystem is in coming up with functions which satisfy the properties required. That nobody has done this yet suggests to me that it is probably very difficult and beyond the scope of a single person’s PhD project.

As another side note, it might also be fun/worthwhile to set up rubber hose cryptography system for mainstream operating systems. A computer’s hard disk is organised into ‘partitions’ (usually just one) where all the information is stored. Rubber hose cryptography organises a hard disk in such a way that more than one partition exists on the hard drive and that each of these different partitions is encrypted and password protected. More than that, each partition functions independently of the others, so when you’re logged in to one of them, you have no knowledge of the other, and more than that, the partition you are logged into appears to take up the entirety of the hard drive. Moreover, the ’empty space’ in the hard drive is filled with random characters which have the appearance of encrypted data. This differs from regular hard drive encryption because if you are compromised and interrogated, you can give a password to a partition which does NOT contain sensitive information, and your interrogators would have no way of knowing that there is sensitive information located in another partition. To the best of my knowledge, this only exists for Linux and BSD systems, and was originally developed to protect activists, whistleblowers, and journalists working in dangerous environments. It would be useful to develop this system for MS Windows and Apple OSX operating systems, since those are the ones more commonly used.

I don’t feel I have the requisite programming expertise to undertake either of these little side-projects (and I certainly don’t believe that either creates enough new knowledge to be PhD-worthy) although my background in mathematics could potentially be useful in designing the systems. If anyone reading this would like to collaborate on either of those projects, please feel free to get in contact with me via the contact link.

Biomechanics

Lastly, those who have been following my recent travels will have noticed that I rather enjoy the sport of speed skating. I skate, I coach, I administer, and I occasionally get to commentate and officiate at races. Skating appeals to me because it is a very technical sport. I’m a naturally very lazy person and if I can go a little faster for no extra effort, then that’s fine by me. This technical-mindedness has made me a much better coach than I ever was a skater, and any training camp with me as the coach will invariably contain many hours of technique analysis.

I simply want to take this to a higher level. I wish to analyse skating technique to the point of being able to find ‘optimal’ technique for any given individual skater (it will vary slightly from person to person because people have different heights, different ratios of tibia-to-femur length, and so on). Then I wish to find out how best to train a person to skate in that optimal technique. Not sure if there’s enough here for a PhD thesis, but it’s a complicated problem which combines fields as diverse as physics, physiology, chemistry, sports science, etc. I just thought it would be fun because I already think about this stuff a lot.

Hi Daniel,

Great post, and good to see you thinking about what you’d like to research.

Firstly, I’d raise a general question. Why do you want your thinking to be part of a PhD? A PhD gives you certain benefits – definite access to academics, generally money, an identity, a clearer path to an academic career, but it also comes with some costs – being forced to conform in your thinking, being surrounded by academics, being forced to learn things you don’t want to learn, sometimes reduced respect. There isn’t a right approach, but sometimes in new fields, there are real advantages in not learning something through a PhD programme.

My main interest is in your first proposal. I did my Masters in History and Philosophy of Science at Melbourne, looking at economic models, including much of the same areas that you mention. It is a really rich area, and what we’re learning about new markets is opening up incredible new real world opportunities (it is one of the major topics on my blog). I’m not active in the academic side of things, but do some searching on to Behavioural Economics, Asymmetric information, market design, auction theory, economic signalling, agency theory. Good names are Schiller, Kahneman, Tversky, Thaler, Taleb. There’s a book that I want to read that came out 6 months ago: Everything I ever needed to know about economics I learned from online dating. The challenge with such a rich subject is narrowing it down to a topic where you can make a novel contribution – it is too easy to end up way too broad, or so narrow it is irrelevant.

Best of luck!

Hi Dan,

Good to hear that you are thinking of doing PhD. Following up on Gus’ question, why do you think PhD is the path toward acquiring knowledge?

In the area of economics, I would say that good economists tend to come from outside. Out of five names Gus has mentioned, at least four didn’t do economics traditionally. Kahneman, Tversky and Thaler are psychologists by profession, and Taleb was an option trader before entering academia. I have an opinion that your insights carry more weight if you can execute it in the real market.