Sochi Special: A Day In The Life

For most people, the olympics is entertainment for two to three weeks every four years, but for the athletes competing (including the countless numbers who don’t make it) it is every day, and often for much longer than four years.

Most of the general public are under the misconception that athletes train all the time, as in – all day long. In a broad sense, this is true – sport is the full time profession for all but a few athletes at the games, but in the sense that athletes are actually out running, jumping, or skating ALL day long, this is untrue. Depending on the sport, an athlete can expect to train about 30 hours a week. This will vary from week to week depending on which part of the training program the athlete is in, and what part of the competition season is currently being experienced. Close to a major competition, an athlete’s training load will typically be less than normal since being tired from training is not conducive to medal winning performances.

I’ve been fortunate enough to have trained and competed in many different sports, some at a very high level. I also have the added perspective of being a coach, and being in a position to design not only individual’s programs, but also broad-scale national development programs, as well as elite programs. I am often struck by just how much good science there is out there, and also by how much of it simply isn’t used.

A typical day for an elite athlete begins with a fairly early wakeup followed by a large, healthy breakfast. Then there is usually a gap of several hours followed by the first training of the day. (This is an ideal scenario, often the scheduling of facilities forces things to be slightly different). Following this, a meal is consumed, usually lunch. The athlete will then rest for most of the early afternoon, grazing on small bits of food and occupying their time with console games or a TV series (for me, it was Guitar Hero and The Office). An evening/late afternoon training will follow, and then dinner. After dinner, athletes usually socialise a bit and continue with their console games and TV. Sometimes they’ll watch live TV at this time, because that’s when the better shows will be on (note how I didn’t say ‘good’), and then they’ll go to bed, ideally at ten or eleven.

Very occasionally there will be a day with three trainings, but when that happens one of those trainings will be less intense, or very short. The average elite athlete can expect one full day off every week, or at least a day with only one, relatively easy training session (like a long, easy bike ride in a large group to share the lead around). “Easy” is a relative term, of course, since a mature athlete with a long background of full-time training is going to find a session that a young developing athlete finds difficult easy. The measuring of the training load is very athlete-dependent.

Many a weekend warrior might balk at this training schedule, labelling elite athletes as soft and pampered. Often this is because, during their school years, they experienced “footy camp” or something similar which would have involved higher training loads, and more training hours (including questionably-effective training methods, and useless macho-man sports psychology, but I digress). Moreover, the weekend warrior would have experienced a significant improvement in their meagre sporting ability immediately following the aforementioned training camp. Of course, weeklong, or even monthlong training camps don’t make elite athletes any more than watching the news makes you an expert in foreign policy. The bottom line here is that these training loads are unsustainable, and for a mature athlete who is generally always riding the knife’s edge between a good training load, and overtraining, these training loads can prove disastrous. Rest and recovery are essential parts of a good training program, and building a competitive elite athlete necessarily demands discipline, sustainability, and science above “go harder than the other guy” attitudes towards training.

What these sessions consist of varies enormously, not just from sport to sport, but also within sports. Most sports will have about one session a day dedicated to the practice of that sport, and the other session will be something else. For example, in athletics, I ran six days a week, and filled in the other sessions with weights twice a week, bike rides twice a week, one deep-tissue massage, and a swim for recovery purposes. Speed skating is unique among sports because a speed skater spends the majority of their training hours not-skating. A major part of this is because there simply isn’t any ice for about half of the year. In addition, because ice skating is so technical, spending a lot of time skating when you’re tired can be counterproductive, as it can cause you to form bad habits with your technique, which can be detrimental if your event depends on speed (all speed skating events do).

Traditionally, speed skaters spend a lot of time in the weights room, often three times a week, and also a lot of time on the bike, whether it be on a watt-bike hammering out a precisely-measured interval program, or on a road bike clocking up thek K’s. Recently, the (very late) realisation that inline skating can be beneficial to ice skating, despite its subtly different technique (read more about the differences here), has resulted in more inline skating being integrated into training programs. Running and plyometrics also feature, but often only once a week due to their relatively high intensity (anyone who has ever done a full plyometrics and imitations program, often called “dryland training” in the ice skating world will know what I mean).

Then there’s the overall structure of the annual plan. At its most basic level, an annual plan consists of a general preparation phase, and a specific preparation phase. In sports with long competition seasons, like team sports with leagues, the specific/competition phase is relatively long, and it can be extremely challenging to keep athletes in good condition throughout a long season, and still peak a little bit for playoffs/finals (if the team is succesful enough to play in them). In sports like speed skating, this is usually easier, since there is a well-defined build up to world championships or the Olympics. In a broad sense, training programs will begin with relatively high volumes and low intensities and then build up to higher intensities and lower volumes as the year wears on. Then, just prior to major competitions, there will be a drop off in overall training load. How sharp this dropoff is varies from person to person, with distance athletes generally tapering quite sharply, while sprinters taper gradually (to allow for the conversion between type IIa and type IIx muscle fibres).

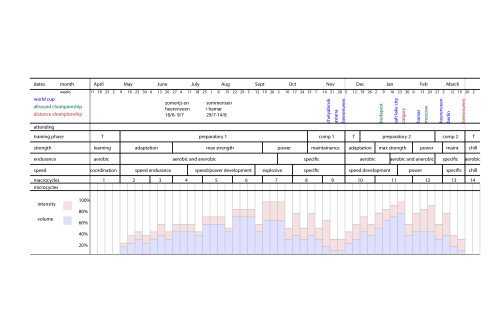

The annual plan I wrote for Danish skater Cathrine Grage for the 2011-2012 season. There are two peaks, one during the first block of World Cup races, and the second for World Single Distance championships (click for larger image).

Within the overall annual plan, there are smaller phases still. Athletes begin by building a base of conditioning appropriate to their event, then depending on the individual, certain aspects of their sport will be targeted whether it be top speed development, or acceleration technique, or something as simple as learning to skate a flat lap-time schedule. These phases can take anywhere from a month to several months, and these plans, to be effective, must be highly personalised. Then going into competition, the plan usually revolves around race simulations, and very specific focus on aspects of racing which will give the athlete a competitive advantage, and their best shot at a good result. Within all of these phases, are macrocycles of typically 3-5 weeks (usually 4) where the training load is gradually increased, then decreased drastically (sometimes by up to a half) for a short time to allow for the athlete to recover, and hopefully for their body to “overcompensate” a bit for the training load, and thus get stronger. This is easier said than done, especially as mature elite athletes are already operating very close to their own limits (and for that matter, the limits of sustainable human performance). Still within these macrocycles are microcycles, usually lasting a week. These are the specifics of the day-to-day grind, and they must be determined in the context of the annual plan, as well as how the athlete is responding to the training.

So what makes a gold medal winning athlete? An orange skin suit? A good training program? At the very top, so many little things contribute to an athlete’s success, that it is difficult to single out individual factors. There are the physical parameters, of course – genetics basically. Anaerobic threshold, VO2 max, maximum power output, lactic acid tolerance, metabolic rate, among many other factors are very difficult or impossible to change, and you’ll find that almost everyone who makes it to the Olympics is physically gifted in some way. But there’s much more to it, of course. I’ve been in sports for a long time, and the list of incredibly gifted athletes that I’ve seen quit before reaching their full potential is longer than I care to imagine; I’ve even coached a few. There are, of course, environmental factors too. Some countries don’t have any long tracks, which makes it challenging to build a long track program. Even with good facilities, the sport is so small in most countries that you might be stuck in a country where the ‘national coach’ doesn’t know anything about ice skating, and was taken from another sport. Similarly, the established skating tradition in your country might be poor, or might favour certain events and distances at the expense of the event that you are most physiologically well-made for. You might even live in a country that isn’t even an ISU member country. Then there are personality factors; you might be averse to cold weather, or temperamental and difficult to work with. Success demands so many things, most of which are completely outside of anyone’s control, to fall right (this statement is generally true outside of sport).

However, there are things an athlete can do to maximise their chance of success. Successful athletes are generally very determined, and persistent. It seems obvious, but quitting is a pretty sure way to not be successful at elite sport. Great athletes are persistent, often to the point of obsessiveness. Great athletes also enjoy what they do. Training day in and day out at a high level is difficult, and there are many days when you just don’t want to get out of bed and put the hours in. Enjoying the sport is an essential intrinsic motivator to keep you going when you’d really rather be doing something else. Great athletes are also focussed – this is one of the greatest differentiators between average athletes and the really good ones. Lots of people at the lower levels of any sport just rock up to training and go through the motions, which is better than doing nothing at all, sure. But truly great athletes can stay concentrated and focussed, knowing the purpose of every rep of every set, and being able to make the link between their training and their goals. They are able to focus all their energies throughout training, and also on the day of competition, able to shut out distraction and energy-sapping worrying from their minds.

Having said all of that, it is still difficult, and even if everything falls into place textbook-style, there is still no guarantee of an Olympic medal. The level of competition is so high and the margins so close, that there is very little to distinguish the performance of the gold medal from someone who just finished within the top ten. In my mind, it is most important that athletes enjoy what they do. In the end, it’s just sport. Maybe you’ll be lucky, and everything will fall into place, and you’ll get an Olympic medal, but maybe not. All you can hope to do is your best, hope that all the dice roll in your favour, and be satisfied with the result. The life of the elite athlete isn’t for everyone, but for those who pursue it, with the right attitude, it promises great reward and fulfilment, no matter what the actual result. In my view, time spent doing something that you enjoy is time well-spent and a life dedicated to a sport you love is a life well-lived.

Don’t forget to click on the sochi2104 tag below to read other articles about these olympics. You may also want to read some of the other ‘Sochi Specials’ which have been very popular, for example the close finish of the mens 1500m has raised questions about the timing equipment used in speed skating, while the controversy surrounding the American’s suits might lead you to read about the speed suits in general terms, or more specifically in an article where I articulate why it is NOT about the suits. Going even further, I break down and analyse the anatomy of a race, using American skating legend Shani Davis as an example.

Leave a comment